What Does Qiyama Mean in Ismailism? (7 Min. Read)

Unveiling the Resurrection: Qiyama as Manifestation of Sublime Realities and Spiritual Awakening

What does Qiyāma mean in Ismaili spirituality? Rather than the end of the world, it is understood as illumination—a spiritual awakening of the human intellect and soul, in which relative outward forms give way to sublime inner realities. Through a short poem and reflections drawn from classical Ismaili thought, this essay explores Qiyāma as a Cycle of Unveiling, inviting seekers to consider how the Imām’s ta’wīl (esoteric interpretation) leads from the veil of religious law toward the realization of true submission and spiritual contentment.

“Contentment (riḍā) and submission (taslīm) are realized when…relativity (iḍāfat) is submerged into reality (ḥaqīqat)…and religious law (sharīʿat) into resurrection (qiyāmat).”

— Sayyidnā Naṣīr al-Dīn Ṭūsī

(Shiʿi Interpretations of Islam, 28)

“Unveiling the Resurrection”

By: Khayal ‘Aly

Written: January 5th, 2026

During the Era or Cycle of Sharī‘a,

how could the great secrets

of Ḥaqīqa be revealed?

It’s true some ta’wīl

was understood and written,

but deeper esoteric wisdoms

were mostly left concealed.

Of course, there always were

Knowers who knew the Truth,

who uttered the most perfect words

that could be spoken.

Those sages anticipated

the Great Resurrection,

when, like today,

humanity was ready to be awoken.

Without a doubt, even now,

not everybody is yet ready —

since the entire Cycle of Qiyāma

will take some time.

But if you wish to be included

in the group of true seekers,

come discover sublime realities

of the Lord Most High.

Unveiling the Resurrection in the Light of Ismaili Gnosis

The poem “Unveiling the Resurrection” presents a distinctly Ismaili understanding of Resurrection (Qiyāma) as a gradual process of unveiling (kashf), rather than a sudden physical end of the world. By centering the idea of ḥaqīqa (Reality), the poem clarifies that resurrection concerns not merely the disclosure of hidden teachings, but the direct apprehension of divine reality by a spiritually and intellectually prepared human being.

The poem begins by recalling the Era or Cycle of Sharīʿa—a period in sacred history governed by law, symbols, and outward religious forms—during which the full disclosure of deeper realities was neither possible nor appropriate. In Ismaili thought, Sharīʿa represents a necessary stage of spiritual education. It disciplines the soul, orders communal life, and preserves faith while deeper realities (ḥaqāʾiq) remain veiled. Classical Ismaili authors describe this phase as the Dawr-i Satr (Cycle of Concealment), characteristic of prophetic eras, in which the exoteric (ẓāhir) dimension of religion predominates and the esoteric (bāṭin) remains largely hidden. The corresponding Dawr-i Kashf (Cycle of Unveiling), however, is associated with the Imāmat and the Qiyāma, for it is the Imām’s divinely ordained role to reveal ta’wīl—the inner meanings of revelation—and to make accessible the esoteric knowledge necessary for spiritual resurrection.1

For this reason, the poem rightly notes that only limited and partial ta’wīl was available during the Era of Sharīʿa, while deeper realities were mostly concealed. Inner meanings were present, but disclosed selectively, in proportion to human readiness. Ta’wīl, in Ismaili doctrine, is not merely interpretive but transformative—a lived spiritual and intellectual operation that enables the seeker to move from symbol to meaning, form to reality, and physical practice to spiritual realization. As articulated in Fatimid Ismaili thought, ta’wīl raises the individual through a succession of resurrections, each awakening corresponding to a higher realization of meaning and mirroring, on a smaller scale, the Great Resurrection itself.2

The poem’s reference to Knowers (ʿārifīn) who knew the full Truth affirms the enduring Ismaili conviction that ḥaqīqa is never absent from the world, even in periods of concealment (satr). Such Knowers safeguarded what the poem calls the “most perfect words,” yet discussed them only within protected circles. This restraint reflects a core Ismaili principle: unveiling without preparedness can lead to confusion or rejection rather than illumination. Concealment, therefore, is not denial of truth, but mercy toward the unready soul.

Central to the poem is its portrayal of Qiyāma as both macrocosmic and microcosmic. As an Ismaili Gnosis article titled “Haqiqati Hajj: The Metaphysical Pilgrimage” explains:

“Understood macrocosmically, the “Day of Qiyama” refers to a cycle (dawr) or period of time (zaman) in which great spiritual secrets and esoteric wisdoms are revealed. As such, Dawr-i Qiyama (Cycle of Resurrection) is also referred to as Dawr-i Kashf (Cycle of Unveiling).

Understood microcosmically, living in a time of Qiyama refers to a true believer’s elevated state of being or consciousness, where he or she is spiritually and intellectually ready and able to worship God at the higher level of Haqiqah (Reality).

When a seeker reaches the stage where they practice their faith in a haqiqati way, they are already living, internally, in the time or cycle of Qiyama, whether they have been completely spiritually resurrected or are still progressing towards that exalted destiny.”3

On the macrocosmic level, Qiyāma refers to a historical cycle—the Cycle of Unveiling—in which the esoteric realities of revelation are disclosed more openly. Classical Ismaili thinkers explain that the cycles of concealment and disclosure alternate “like night and day,” culminating ultimately in the Qiyāmat-i Qiyāmat (Resurrection of Resurrections), when unveiling reaches its fullest expression.4

On the microcosmic level, however, Qiyāma refers to an inner, personal resurrection—an elevated state of consciousness in which a believer becomes capable of worshipping God at the level of ḥaqīqa. When a seeker begins to practice faith in a ḥaqīqatī way, they are already living inwardly in the time of resurrection, even as the collective process continues to unfold. In this sense, resurrection is not only an event in sacred history, but a transformation of the human intellect and soul—a passage from ordinary human capacity toward what Ismaili thinkers describe as the “first degree of angelic power.”5

The poem’s acknowledgment that “not everybody is yet ready” reflects a central Ismaili insight: resurrection is gradual, selective, and—at least with respect to one’s physical life—non-coercive. One “Day” of God may encompass a thousand years of unfolding effects and consequences (cf. the Ismaili ta’wīl of Qurʾān 22:47). Ismaili tradition even speaks of the anticipated collective resurrection as having begun secretly, with its consequences unfolding over long periods—intellectually, ethically, and civilizationally.

In this light, Qiyāma does not signify the destruction of the physical world, but its spiritualization. As explained in the Ismaili text Kalām-i Pīr:

“At the time of the Great Resurrection (qiyāmat-i qiyāmat), when everything will be revealed, there will be no hindrance, either belonging to the physical world, the ẓāhir, or to the spiritual sphere, the bāṭin, before the eyes of the people.…”6

The exponential growth of knowledge, the abstraction of information from material form, and the unprecedented expansion of human intellectual capacity may all be understood, from an Ismaili perspective, as signs of the unfolding Epoch of Knowledge (Dawr-i ʿIlm). In the light of Ismaili gnosis, every true discovery is rooted in the activity of the intellect and soul, aided by divine support (ta’yīd) through the Holy Spirit (rūḥ-i qudus), and ultimately linked to ta’wīl—the unveiling of deeper esoteric wisdoms and the realities of ḥaqīqa—through the agency of the Qāʾim-i Qiyāmat (Lord of the Resurrection).7

As explained in the Ismaili Gnosis article “Esoteric Apocalypse (Part 1),” the coming of the Qāʾim marks a transition from an Epoch of Practice, oriented primarily around outward actions (ʿamal) and material forms, to an Epoch of Knowledge, characterized by an unprecedented abundance and accessibility of ʿilm. In this Cycle of Qiyāma, deeper levels of ta’wīl are no longer confined to a select few but become increasingly disclosed, fulfilling the Qurʾānic declaration:

“Do they await its ta’wīl? The day its ta’wīl comes, those who had forgotten it before will say: ‘Verily, the Messengers of our Lord came with the Truth’” (Qur’ān 7:53).

Through this unveiling of ta’wīl, humanity becomes increasingly able to recognize the Truth (ḥaqīqa) within the messages of all Prophets. Knowledge that was once guarded under conditions of secrecy may now be shared more openly, as the Cycle of Resurrection and Unveiling brings about a new spiritual condition in which wisdom is disseminated more freely and in greater abundance.

It is in this sense that Sayyidnā Nāṣir-i Khusraw—who lived historically within the Cycle of Sharīʿa, yet, as an enlightened dāʿī (summoner), or ḥujjat, of the Imām, already inhabited the inner reality of resurrection—spoke of the “Day of True Resurrection” as a time “in which the wise take such delight,” when “the shadows of ignorance will be lifted from humanity by the light of His knowledge,” in fulfillment of the divine promise that “the earth will be illumined by the light of its Lord” (Qur’ān 39:69). Nāṣir-i Khusraw continues:

“When the Resurrection comes, the earth will be illumined. … That earth is dark now, but it will shine forth, and in its shining all the obscurity of conflicting interpretations will be dispelled.”8

Taken as a whole, the poem and the teachings it reflects present Resurrection not as a distant or instantaneous event, but as a living and unfolding reality—one that has already begun, yet continues to mature across time. While the Cycle of Qiyāma may extend over a long duration, its light is not reserved for a future generation alone. Those who wish to truly benefit from this sacred cycle, and to participate consciously in its work of unveiling, are called to come forward as sincere seekers.

To seek the “sublime realities” (ḥaqāʾiq ʿāliyyah) named in the poem is to align one’s intellect, soul, and practice with the deeper truths now being disclosed through the ta’wīl of the Imām. It is to move beyond mere information toward realization, beyond outward conformity toward inward awakening. Resurrection, therefore, is not only something awaited at the end of sacred history; it is something to be prepared for, entered, and increasingly lived by those who sincerely seek spiritual communion with the Lord Most High (Rabb-i Aʿlā).

سَبِّحِ ٱسْمَ رَبِّكَ ٱلْأَعْلَى

Sabbiḥi isma rabbika al-A‘lā

“Glorify the name of your Lord,

The Most High”

«Qur’ān 87:1»

Ya ‘Ali Madad,

Khayāl ‘Aly

January 7, 2026

Follow on Instagram:

khayal.aly | ismaili.poetry

ismailignosis | ismailignosis.blog

Scroll down for recommended resources on resurrection

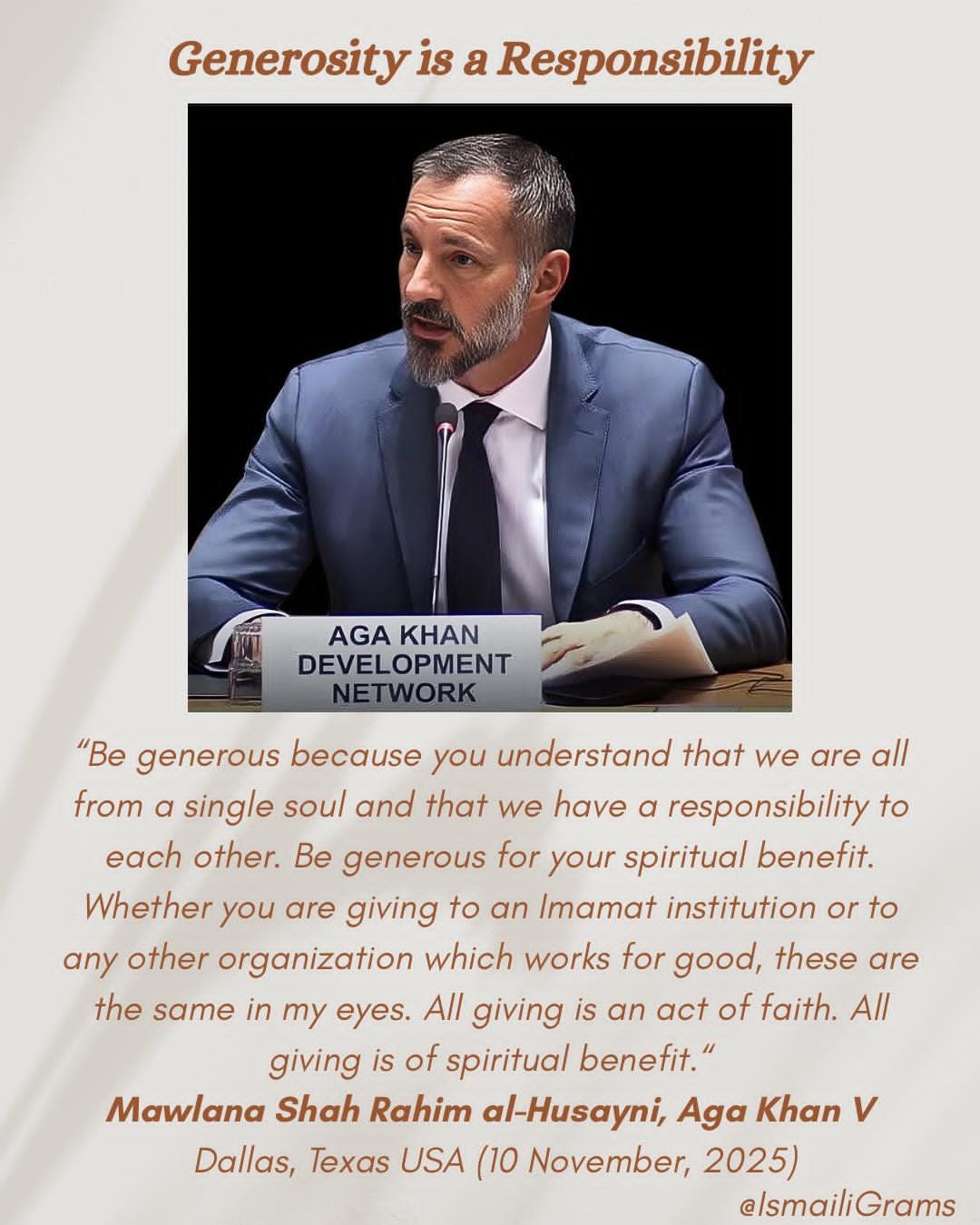

Support Ismaili Gnosis

in Publishing Articles

“Whether you are giving to an Imamat institution or to any other organization which works for good, these are the same in my eyes. All giving is an act of faith. All giving is of spiritual benefit.”

— Imām Shāh Raḥīm al-Ḥusaynī⁽ᶜ⁾

(Dallas, Texas, November 10, 2025)

RECOMMENED RESOURCES

ON RESURRECTION

Naṣīr al-Dīn Ṭūsī (with Ḥasan-i Maḥmūd), Rawḍa-yi Taslīm, translated by S.J. Badakhchani as Paradise of Submission: A Medieval Treatise on Ismaili Thought (London and New York, I.B. Tauris, in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2005, 69.

Elizabeth R. Alexandrin, Walāyah in the Fāṭimid Ismāʿīlī Tradition (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017), 193; the relevant passage is also reproduced in Khayāl ‘Aly, “Laylat al-Qadr in Ismaili Spiritual Life” (2024), published on Ismaili Gnosis; see section titled “Ismaili Ta’wīl: Succession of Resurrections.”

Khayāl ‘Aly, “Haqiqati Hajj: The Metaphysical Pilgrimage” (2024), published on Ismaili Gnosis; see section titled “Esoteric Purpose of the Pilgrimage.”

Khayrkwāh-i Harātī, Kalām-i Pīr, trans. W. Ivanow, p. 41, quoted in Ismaili Gnosis, “Esoteric Apocalypse (Qiyāmah): Ismāʿīlī Muslim Perspectives on the ‘End of the World’ (Part 2)” (2012), published on Ismaili Gnosis; see section titled “The Abolishment of the Ranks of Faith (Ḥudūd al-Dīn).”

Ismaili Gnosis, “Esoteric Apocalypse (Part 2); see section titled: “Ḥaḍrat Qā’im al-Qiyāmah: Lord of the Resurrection.”

Nāṣir-i Khusraw, Kitāb Jāmi‘ al-Ḥikmatayn, translated by Eric Ormsby as Between Reason and Revelation: Twin Wisdoms Reconciled (London and New York, I.B. Tauris, in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 20012), 153.

This was a beautifully written and very accessible explanation of Qiyāma. It made a complex concept feel clear, and spiritually meaningful. I especially appreciated how the idea of resurrection as an inner awakening and gradual unveiling was explained so simply and thoughtfully. This was a nice easy to read and helpful article.